When you google an image of “Nature,” what comes up?

When you google an image of “Nature,” what comes up?

Probably a glamorous picture of a national park or a scenic image with a pristine sunset in the background. But we all know this is not what nature really looks like. Although the views may be beautiful, I have hardly ever gone hiking and discovered a wilderness as heavenly as the one these images depict. In my experience, nature is much rawer and more genuine than that which is featured on google. Of course, it depends on the person, but generally people try to capture a picture that magnificently depicts the wild because it is more aesthetically pleasing for their Instagram post. Why do we adore such heavily stylized or “posed” photos, and when did this start? In this essay, I will explore environmental discourse, human patterns and behavior over the past 250 years, and the problems that arose through the building of America. In addition, I will be using the words “nature,” “environment,” and “wilderness” interchangeably.

If we jump back 250 years in American and European history, people were not worshipping the woods like we do now. The last thing that was desired at this time, was seeking the “wilderness experience” we value so much today. As late as the eighteenth century, “wilderness” had a negative connotation, evoking feelings of isolation, fear, savagery, and desolation. “Waste” was the word’s closest synonym, explained in William Cronon’s, The Trouble with Wilderness (Cronon, W. 1996). These “wastelands” were not just left alone out of fear, however. At the heart of our country is the spirit of hard work, progression, and improvement of our quality of life. These foundational characteristics were sewn and grown during this time, along with the social and ethical issues we still face today. “Unused land was, for Europeans, unowned land, available for improvement under colonial rule.

Productive land was expected to look a certain way, like typical farms or managed forests in the Old World. Because of these preconceived notions, lands that had been systematically used and improved by native peoples, before the conquistadores arrived in Vera Cruz, Mexico, came to be defined and designated as “baldios” or “yermas”: wastelands. Wasted land was available for improvement, indeed by implication it demanded improvement (Sluyter 1999) and therefore appropriation by the colonizers.”

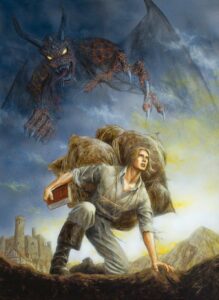

As we enter the nineteenth century, this “frontier” view of nature and true wilderness was completely switched around. While the frontier was strangely American and had its parallels with European culture and ideas, a new term was implemented into society at this point in history. During this time, we were introduced to the idea of “the sublime,” which can be closely related to how we view nature through modern lenses. The sublime is a social construct that essentially romanticizes nature. Much of today’s environmentalist discourse was created from the wilderness intellectual movements such as romanticism and post-frontier ideology. “Wilderness had once been the antithesis of all that was orderly and good – it had been the darkness, one might say, on the far side of the garden wall – and yet now it was frequently likened to Eden itself.” (Cronon, W. 1996). Many people living during this frontier age made many religious and spiritual connections to wilderness, a common theme we still see today. However, their connection was much more negative and pessimistic, recognizing it as the place Adam and Eve were “cast out” to, and created this image of struggle and vulnerability.

The myth of the “frontier” almost directly identified with the male gender. In the wilderness, a man could be rugged and grow stronger by being subjected to the natural elements. It was believed that only a man could handle these challenges and that he “fit” into the ecosystem of the wilderness.

The myth of the “frontier” almost directly identified with the male gender. In the wilderness, a man could be rugged and grow stronger by being subjected to the natural elements. It was believed that only a man could handle these challenges and that he “fit” into the ecosystem of the wilderness.

Man may have over-glorified (or over-estimated) his placement on the food chain and viewed himself as having the ability to tame the untamable, but regardless of the empty truth that holds, this idea is a concept we recognize as an underlying belief in our society. Masked in modernity, the concepts of masculinity have been developed from these “American Frontier” origins. Ideas such as hunting being a task for a man, or a task only a man could complete, even though this is a human concept and not at all true in nature.

Wilderness serves as a foundation on which so many sacred values of modern environmentalism rest. The evaluation, or rather critique, of modernism that is a notable contribution of environmentalists often appeals to the idea that the state of wilderness is the unit in which we measure our failure or shortcomings as a species. Wilderness is a landscape of authenticity and freedom that allows us to rediscover ourselves, which has been lost in our artificial lives. Not only do we seek asylum in nature, but we have also transformed it into a commodity for our selfish use. One can observe this through the tragedy of pollution and how it litters the environments of our planet. To chase this idea of “the sublime,” we have created and preserved national parks to serve as our glimpse into heaven when, in reality, they are our playgrounds.

There is trash left behind from inexperienced campers and irresponsible tourists, amenities built to accommodate for our needs which now occupy the previous locations of local flora and fauna, and habitats disrupted by foot traffic, loud noises, and curiously ignorant visitors. The hustle and bustle of modern lifestyles have stretched into nature, a victim of our expansion. The spirit of the frontier lives on through our desire to turn nature into something more efficient, more appealing, more consumer-friendly, and something that can be tamed. We have commercialized nature and exposed it to consumerism, throwing off its natural equilibrium and leaving it looking like a Vegas showgirl.

There is trash left behind from inexperienced campers and irresponsible tourists, amenities built to accommodate for our needs which now occupy the previous locations of local flora and fauna, and habitats disrupted by foot traffic, loud noises, and curiously ignorant visitors. The hustle and bustle of modern lifestyles have stretched into nature, a victim of our expansion. The spirit of the frontier lives on through our desire to turn nature into something more efficient, more appealing, more consumer-friendly, and something that can be tamed. We have commercialized nature and exposed it to consumerism, throwing off its natural equilibrium and leaving it looking like a Vegas showgirl.

Social construction is everywhere, whether we recognize it or not. Imagine a picture of a wooded trail overlooking a lake at sunset. This is a typical image you’d find on the internet, like I described in my introduction. However, how much of this image is natural? Questions we probably don’t ask, but should, include:

How did this trail get here? This clearing was most likely not naturally occurring. Is the lake man-made?

Is the lake dammed? If the lake isn’t dammed by a human construction, and let’s say beavers created it, were the beavers introduced into this environment? Therefore, are they “natural?”

Was the area reforested, or is this flora naturally occurring?

To say that some claim or concept that we think of as “natural” actually might be “socially constructed.” It is not hard to find clues of social construction if you have the right questions to ask and proper guidance. Here are some questions to help you determine if something is socially constructed (Hacking, I. 1999):

Is this claim or concept natural, inevitable, timeless, and universal?

If not, at what point was it invented? Under what conditions?

What are the social, political, or environmental effects of believing that this claim or concept is true, natural, or inevitable?

Would we be better off doing away with the concept altogether, or rethinking it in a fundamental way?

The common pattern in my above example questions is that of human interference. There are many ways to define “nature,” my personal belief being that which has not experienced human intervention. Raymond William points out, (Williams, R. 1976) the word nature has at least three common usages:

- the essential quality and character of something.

- the inherent force which directs either the world or human beings or both. iii. the material world itself, taken as including or not including human beings. Take the example of the black squirrels here in Kent, Ohio. Would you consider those natural? They were, after all, introduced into this environment after being removed from their place of origin. A fun exercise to try that gives you a clearer look into the minds of so-called “nature lovers,” is to google reviews of a selected national park. Look at the 4–5-star reviews and focus on why they enjoyed them so much. A common theme you will find is people were mostly satisfied when they had access to a variety of different amenities (playground, bathrooms, shopping, restaurants) within a relatively close radius. Then, look at the 1-2-star reviews and see why people hated their experience so much. Some hilarious comments I found were along the lines of, “too many bugs,” “trial was not well maintained,” and my personal favorite, “I’ve never been there.” I think you will find that the locals have a different perspective than the tourists, as well.

Geographers Barnes and Duncan (Barnes, T. J., and J. S. Duncan 1992) define discourses as “frameworks that embrace particular combinations of narratives, concepts, ideologies, and signifying practices.” In simpler terms, this means statements and texts are not just representations of the physical world, but rather hold power in their meanings and create the ideas we believe today. Discourses are stories, but its social context of their creation has disappeared over time, and we now recognize them as fact or truth.

Environmental discourse analysis is a technique used to examine these constructions of nature that attempts to reverse this trend toward the constancy of discourses by studying them and attempting to focus the ways on which social context influences their construction and upkeep. This is a nontraditional approach because it focuses on the concepts (ex. health, sustainability, hunger) and sources of information (ex. government experts, scientific laboratories) that other accounts take for granted and assume to be independent and reliable.

A social constructionist approach to the environment is not only interested in discourses, but the social institutions to which they are tied.

A social constructionist approach to the environment is not only interested in discourses, but the social institutions to which they are tied.

In modern society, environmental discourses are increasingly linked to influential institutions such as governments, schools, hospitals, and laboratories. These establishments are owners of power that are in the business of managing the relationship between environment and society, not so much by telling people what can and cannot be done, but instead by implanting and solidifying specific understandings of what is and is not true. Where this has caused problems, is in social justice and racial equality, as an example.

The idea of discourse is seen in issues of ethics, environment, politics, inclusivity, racial injustice, and so on. I implore the readers of this article to further their knowledge on this subject and explore the sources listed in the bibliography. It is crucial to understand that we as a species have been responsible for the degradation of our planet, but we will also have to be part of the solution. We cannot separate a human problem from a human solution. Despite differing views, our future will be grown in labs, on farms, and in factories, right where our problems started.

Through my research and explanations of the discussed topics, it is my hope that you have gained a better understanding of how human social concepts and psychology relates to how we view nature in the present, and how that view has evolved over the past centuries. It is important to remember to view this anthropogenic period on a scale of geologic time. Although we have created damage that seems irreversible, the extinction we are accelerating isn’t the planet’s, but our own.

It is time we go into the wilderness, not seeking a metaphysical experience, nor a journey of manliness, or a quest for cosmic understanding, but rather a universal observation of our effect on the planet, as humans. As the main contributor to these environmental changes and fluctuations, it is our moral obligation to recognize and reverse the damage we have caused, for the sake of our existence.

Bibliography

Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness: A response. Environmental History, 1(1), 47.

Williams, R. (1976). Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sluyter, A. (1999). “The making of the myth in postcolonial development: Material conceptual landscape transformation in sixteenth century Veracruz.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 89(3): 377–401.

Hacking, I. (1999). The Social Construction of What? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Barnes, T. J., and J. S. Duncan (1992). “Introduction: Writing worlds.” In T. J. Barnes and J. S. Duncan (eds.) Writing Worlds: Discourse, Text, and Metaphor in the Representation of Landscape. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–17.

Robbins, P., Hintz, J., & Moore, S. A. (2014). Environment and Society. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.