Title: Universal Harvester

Author: John Darnielle

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Publication Date: February 7, 2017

Rating:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

“A few rows of corn will muffle the human voice so effectively that, even a few insignificant rows away, all is silence,” writes John Darnielle in his second novel Universal Harvester, a follow up to his debut, Wolf in White Van. The Mountain Goats singer-songwriter creates a story that quietly echoes across generations, dealing in loss, grief and the attempts to project normalcy that follow such things.

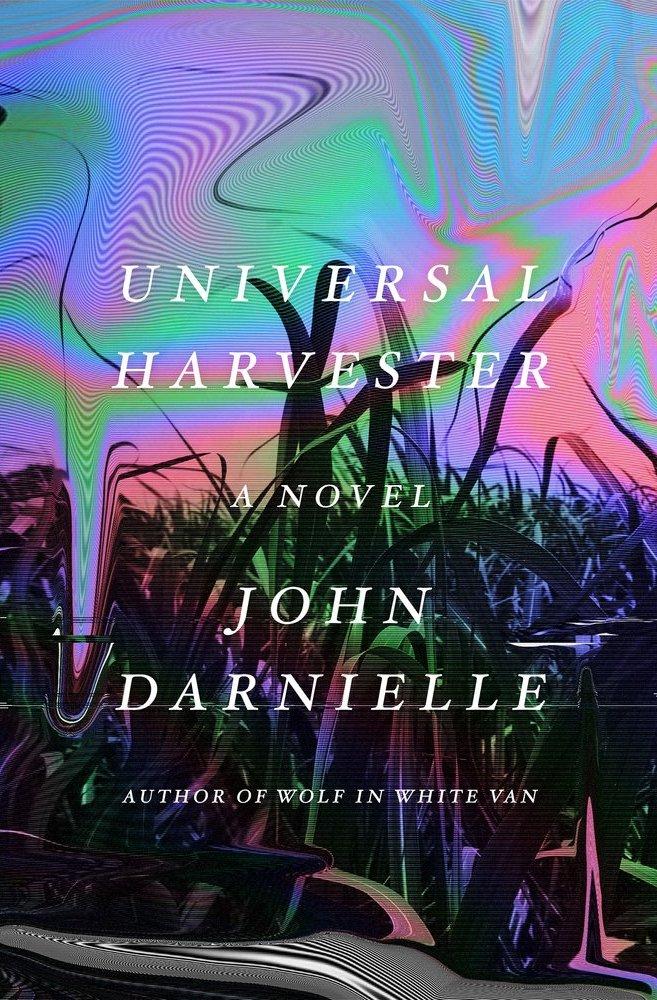

The mystery of the story stays within the bounds of the Iowa corn that surrounds its characters. Its jacket design hints at this, being a warped, multicolored image of corn, as if having been taken from an old, deteriorating VHS tape.

The premise explained to those reading the inside cover of Universal Harvester is that a 22-year-old named Jeremy lives in a small town called Nevada (pronounced Ne-vay-da) and works in a video rental store in the late 1990s.

The quiet tranquility of Jeremy’s life and work is interrupted when one customer brings in a tape and complains that there is something on it that shouldn’t be there. Then another customer brings in a different tape, with a similar complaint.

What Jeremy finds when he watches are pieces of video spliced onto the tape. The scenes are dark, uncomfortable and unsettling, set in a barn that looks to be just outside of town.

Universal Harvester transforms from one book into another as it moves from beginning to end. What begins as a mystery or horror novel slowly becomes a case study in grief and loss spanning the better part of 50 years.

The novel moves back and forth through time over four parts, two of which focus on Jeremy in his present, two of which explore the past and the future of the story.

Much of Jeremy’s story involves the rituals he keeps to in the years after his mother’s death. He goes to work, he goes home, has dinner with his father, watches a movie and goes to bed for the next day.

Part two of Universal Harvester explores the past, and sets up the coping mechanism for another character losing their mother. The novel does not draw a throughline for its audience. Darnielle describes in detail the things certain characters do, slowly peeling back layers, and when in context of the mystery Jeremy faces, the reason behind the videos takes shape.

Darnielle’s narration mostly describes the actions and feeling of characters, but very little is shown of their actual thoughts. In one such example, “Steve listened to the short silence after he’d said it; it was a rift in something. Jeremy felt it too. They almost always had dinner together. It gave shape to their days.”

This style of narration is periodically broken when an inexplicable first person narration comes into the novel, separate from the third-person that makes up the bulk of the novel. The owner of this voice is not apparent until the very end of Universal Harvester.

I imagine the feeling one gets from this sudden change in perspective is similar to the disorientation one must feel when suddenly finding themselves watching black and white footage of hooded figures shuffling around an old barn, where She’s All That had been playing just previously.

The most frustrating part about the novel is the characters’ refusal of all calls to action. Several times characters think about what they would do were they in a Hollywood film, only to remind themselves that they are not in a Hollywood film.

This is the right thing for these characters to think, of course. They are not in a blockbuster movie, and following the actions characters in one would not fit in Universal Harvester. The emotional weight and inertia however, has impact and meaning.

The slow build of emotional weight and concern for these quiet, unassuming people may explain why, as I turned to page 200, I suddenly burst into tears at the first two lines of text. I am still unsure why, but I do know that it felt like a small moment of catharsis within the last 20 pages of the novel to read this small statement of anger and despair.

Universal Harvester, with its halting starts and stops, requires patience and trust that Darnielle is showing the reader what is necessary for the whole picture, even if it is not immediately apparent why.

It is a story that demands slow, thoughtful attention to its details – the antithesis of the way a mystery begs to be uncovered as quickly as possible.

It is still fine to read that way, but it feels as if to fully understand, readers must stop and stand among the stalks of corn and see and hear nothing but what is directly in front of themselves – to exist in each moment as it comes – for me, that is the crux of fully understanding Universal Harvester.